Introduction

Dental anatomy or anatomy of teeth is a field of anatomy dedicated to the study human teeth structures. The development, appearance, and classification of teeth fall within its purvue, though the function of teeth as they contact one another is referred to as dental occlusion. Tooth formation begins prior to birth and their eventual morphology is dictated during this time. Dental anatomy is also a taxonomical science; it is concerned with the naming of teeth and the structures of which they are made. This information serves a practical purpose when rendering dental treatment.

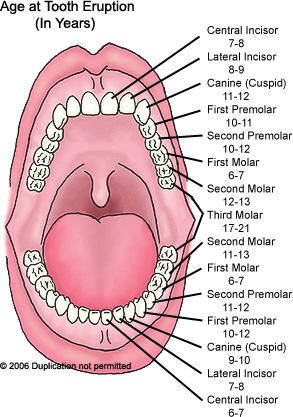

Usually, there are 20 primary ("baby") teeth and 32 permanent teeth. Among primary teeth, 10 usually are found in the maxilla and the other 10 in the mandible. Among permanent teeth, 16 are found in the maxilla and the other 16 in the mandible. Most of the teeth have identifiable features that distinguishes them from others.

Tooth development

Radiograph of lower right (from left to right) third, second, and first molars in different stages of development.

Tooth development is the complex process by which teeth form from embryonic cells, grow, and erupt into the mouth. Although many diverse species have teeth, non-human tooth development is largely the same as in humans. For human teeth to have a healthy oral environment, enamel, dentin, cementum, and the periodontium must all develop during appropriate stages of fetal development. Primary (baby) teeth start to form between the sixth and eighth weeks in utero, and permanent teeth begin to form in the twentieth week in utero.[1] If teeth do not start to develop at or near these times, they will not develop at all.

A significant amount of research has focused on determining the processes that initiate tooth development. It is widely accepted that there is a factor within the tissues of the first branchial arch that is necessary for the development of teeth.[2] The tooth bud (sometimes called the tooth germ) is an aggregation of cells that eventually forms a tooth and is organized into three parts: the enamel organ, the dental papilla and the dental follicle.[3]

The enamel organ is composed of the outer enamel epithelium, inner enamel epithelium, stellate reticulum and stratum intermedium.[3] These cells give rise to ameloblasts, which produce enamel and the reduced enamel epithelium. The growth of cervical loop cells into the deeper tissues forms Hertwig's Epithelial Root Sheath, which determines the root shape of the tooth. The dental papilla contains cells that develop into odontoblasts, which are dentin-forming cells.[3] Additionally, the junction between the dental papilla and inner enamel epithelium determines the crown shape of a tooth.[4] The dental follicle gives rise to three important entities: cementoblasts, osteoblasts, and fibroblasts. Cementoblasts form the cementum of a tooth. Osteoblasts give rise to the alveolar bone around the roots of teeth. Fibroblasts develop the periodontal ligaments which connect teeth to the alveolar bone through cementum.[5]

Tooth development is commonly divided into the following stages: the bud stage, the cap, the bell, and finally maturation. The staging of tooth development is an attempt to categorize changes that take place along a continuum; frequently it is difficult to decide what stage should be assigned to a particular developing tooth.[2] This determination is further complicated by the varying appearance of different histologic sections of the same developing tooth, which can appear to be different stages.

Identification

Nomenclature

Teeth are named by their set, arch, class, type, and side. Teeth can belong to one of two sets of teeth: primary ("baby") teeth or permanent teeth. Often, "deciduous" may be used in place of "primary", and "adult" may be used for "permanent". "Succedaneous" refers to those teeth of the permanent dentition that replace primary teeth (incisors, canines, and premolars of the permanent dentition). Succedaneous dentition would refer to these teeth as a group. Further, the name depends upon which arch the tooth is found in. The term, "maxillary", is given to teeth in the upper jaw and "mandibular" to those in the lower jaw. There are four classes of teeth: incisors, canines, premolars, and molars. Premolars around found only in permanent teeth; there are no primary premolars. Within each class, teeth may be classified into different traits. Incisors are divided further into central and lateral incisors. Among premolars and molars, there are 1st and 2nd premolars, and 1st, 2nd, and 3rd molars. The side of the mouth in which a tooth is found may also be included in the name. For example, a specific name for a tooth may be "primary maxillary left lateral incisor."

Numbering systems

There are several different dental notation systems for associating information to a specific tooth. The three most commons systems are the FDI World Dental Federation notation, Universal numbering system (dental), and Palmer notation method. The FDI system is used worldwide, and the universal is used widely in the USA.

Although the Palmer notation was supposedly superseded by the FDI World Dental Federation notation, it overwhelming continues to be the preferred method used by dental students and practitioners in the United Kingdom.[6] It was originally termed the "Zsigmondy system" after the Austrian dentist Adolf Zsigmondy who developed the idea in 1861, using a Zsigmondy cross to record quadrants of tooth positions.[7]. The Palmer notation consists of a symbol (┘└ ┐┌) designating in which quadrant the tooth is found and a number indicating the position from the midline. Permanent teeth are numbered 1 to 8, and primary teeth are indicated by a letter A to E. The universal numbering system uses a unique letter or number for each tooth. The uppercase letters A through T are used for primary teeth and the numbers 1 - 32 are used for permanent teeth. The tooth designated "1" is the right maxillary third molar and the count continues along the upper teeth to the left side. Then the count begins at the left mandibular third molar, designated number 17, and continues along the bottom teeth to the right side. The FDI system uses a two-digit numbering system in which the first number represents a tooth's quadrant and the second number represents the number of the tooth from the midline of the face. For permanent teeth, the upper right teeth begin with the number, "1". The upper left teeth begin with the number, "2". The lower left teeth begin with the number, "3". The lower right teeth begin with the number, "4". For primary teeth, the sequence of numbers goes 5, 6, 7, and 8 for the teeth in the upper left, upper right, lower right, and lower left respectively.

As a result, any given tooth has three different ways to identify it, depending on which notation system is used. The permanent right maxillary central incisor is identified by the number "8" in the universal system. In the FDI system, the same tooth is identified by the number "11". The palmer system uses the number and symbol, 1┘, to identify the tooth. Further confusion may result if a number is given on a tooth without assuming (or specifying) a common notation method. Since the number, "12", may signify the permanent left maxillary first premolar in the universal system or the permanent right maxillary lateral incisor in the FDI system, the notation being used must be clear to prevent confusion.

Anatomic landmarks

Crown and root

The tooth is attached to the surrounding gingival tissue and alveolar bone (C) by fibrous attachments. The gingival fibers (H) run from the cementum (B) into the gingiva immediately apical to the junctional epithelial attachment and the periodontal ligament fibers (I), (J) and (K) run from the cementum into the adjacent cortex of the alveolar bone.

The crown of a tooth can be used to describe two situations. The anatomic crown of a tooth is designated by the area above the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) and is consequently covered in enamel. Also, it is possible to describe the clinical crown of a tooth as any parts visible in the mouth, but frequently the anatomic crown is meant when the term is used. The majority of the crown is composed of dentin, with the pulp chamber found in the center. The crown is only found within bone before eruption into the mouth. Afterwards, it is almost always visible.

The anatomic root is found below the cementoenamel junction and is covered with cementum, whereas the clinical root is any part of a tooth not visible in the mouth. Similarly, the anatomic root is assumed in most circumstances. Dentin composes most of the root, which normally have pulp canals. The roots of teeth may be single in number or multiple. Canines and most premolars, except for maxillary first premolars, usually have one root. Maxillary first premolars and mandibular molars usually have two roots. Maxillary molars usually have three roots. The tooth is supported in bone by an attachment apparatus, known as the periodontium, which interacts with the root.

Surfaces

Surfaces that are nearest the cheeks or lips are referred to as facial, and those nearest the tongue are known as lingual. Facial surfaces can be subdivided into buccal (when found on posterior teeth nearest the cheeks) and labial (when found on anterior teeth nearest the lips). Lingual surfaces can also be described as palatal when found on maxillary teeth beside the hard palate.

Surfaces that aid in chewing are known as occlusal on posterior teeth and incisal on anterior teeth. Surfaces nearest the junction of the crown and root are referred to as cervical, and those closest to the apex of the root are referred to as apical. The words mesial and distal are also used as descriptions. Mesial signifies a surface closer to the median line of the face, which is located on a vertical axis between the eyes, down the nose, and between the contact of the central incisors. Surfaces further away from the median line are described as distal.

Cusp

A cusp is an elevation on an occlusal surface of posterior teeth and canines. It contributes to a significant portion of the tooth's surface. Maxillary and mandibular canines have one cusp. Maxillary premolars and the mandibular first premolars usually have two cusps. Mandibular second premolars frequently have three cusps--- one buccal and two lingual. Maxillary molars have two buccal cusps and two lingual cusps. A fifth cusp that may form on these teeth are known as the cusp of Carabelli. Mandibular molars may have five or four cusps

Thursday, October 4, 2007

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)